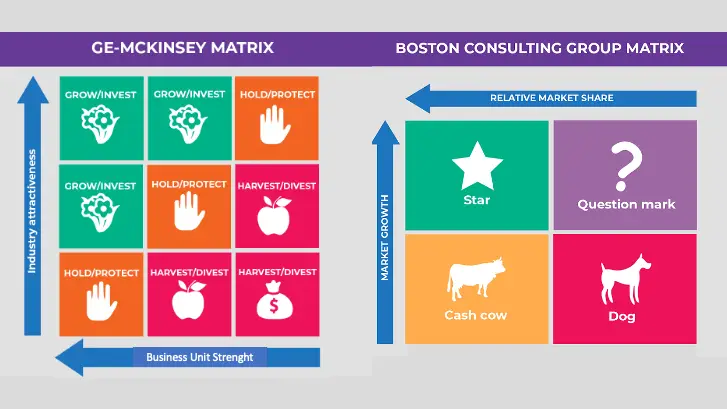

There are many shortcomings that are associated with BCG portfolio evaluation. These observed weaknesses of BCG created the obvious need for more probing techniques of business strategy evaluation. Other approaches include General Electric Motor (GE) approach and the life cycle matrix approaches, which take care of some of BCG”s weaknesses.

Table of Contents

BCG portfolio evaluation

The Need for Other Techniques of Strategy Evaluation

There is need for other techniques of strategy evaluation. This need arises out of the observable weaknesses or shortcomings of BCG growth share matrix.

The Lifecycle Matrix

Evaluating Corporate Strategy by Using More Probing Factors

a. The BCG 4-cell matrix is based on high-low classification. This hides the fact that there are “average” growth rates to be market leaders may be getting stronger while others are getting weaker. A few one-time starts or cash cows have ended up in bankruptcy. Hence, the characteristics to assess are the trend in a firm”s relative market share, i.e., is it gaining ground or losing ground and why? This particular weakness of BCG can be corrected by indicating each business”s present and future position in the matrix.

a. Bell and Hammnd (1979) particularly argue that BCG matrix is not a reliable indicator relative to investment opportunity across business units. They state that investing in a star is not necessarily more attractive than investing in a lucrative cash cow.

b. The matrix results are silent over when a question mark business is a potential winner or being likely loser. The matrix also says nothing about a shrewd investment becoming a string dog, star or cash cow.

c. The connection between relative market share and profitability is not as light as the experience curve effect implies.

d. The importance of cumulative production experience in lowering unit cost varies from industry to industry

e. A thorough assessment of the relative long-term attractiveness of business units in the business portfolio requires an examination of more than just marketing growth and relative share variables.

f. Being a market leader in a slow-growth industry is not a sure guarantee of cash status because

(i) the investment requirements of a hold-and-maintain strategy, given the impact of information on the cost of replacing worn-out facilities and equipment, can soak up much, if not all, of the available internal cash flow, and

(ii) as the market matures, competitive forces often stiffen, and ensure a vigorous battle for volume and market share, can shrink profit margins and surplus cash flows.

Consequent to these shortcomings, an alternative approach that avoids some of the shortcomings of the BCGs growth can be sought with the help from the consulting firm of McKinley and company. The GE effort is a 9-cell portfolio matrix based on the two dimensions of long-term product market attractiveness and business strength/ competitive position.

In the GE 9-cell matrix, as shown in Fig. 10 the area of the circles is proportional to the size of the industry, and the pie slices within the circles reflect the business market share.

The vertical axis represents each industry”s long-term attractiveness.

This is defined as a composite weighting of market growth rate, market size, historical and projected industry profitability, market structure and competitive intensity, economies of scale, seasonality and cyclical influences, technological and capital requirement, emerging threats and opportunities, and social environmental and regulatory influences.

In this procedure, each industry is assigned attractive importance and each business is rated on each factor, using a 1 to 5 rating scale. A weighted composite rating is thus obtained.

Example:

Thus, each business is rated using this approach to arrive at a measure of business strength and competitive position. The competitive values for long-term product market attractiveness and business/competitive position are then used to plot each business’s position in the matrix.

The Corporate Strategy Implication

(1) The vertical lines consisting of three cells at the upper left indicate that long-term industry attractiveness and business strength/competitive position are favourable. The businesses in these zones are given a high priority in terms of fund allocation.

(2) The second zone, i.e., the un-shaded zone, comprising these three cells which usually carry medium investment allocation. The strategy to be adopted here is hold-and maintain.

(3) The third zone, i.e. the horizontal lines, is composed of the 3 cells in the lower right corner of the matrix.

The strategy prescription here is typically harvest or divest. However, in every exceptional case, such a business can be rebuilt or repositioned using a turn around approach.

The 9-cell GE approach has some merits. It is a 3-cell GE approach which is as follows:

a. It allows for intermediate ranking between high and low, and between strong and weak.

b. It considers much wider varieties of strategically relevant variables.

c. It emphasis channeling of corporate resources to those businesses that combine medium-to-high product-market attractiveness with average-to-strong business strength or competitive position. The

fact is that the greatest probability of competitive advantage and superior performance lies in these combinations.

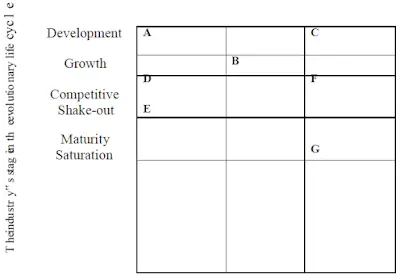

In order to identify a developing winner type of business, Hofer (1978) has developed a 15-cell matrix in which business is plotted in terms of stage of industry evolution and competitive position. This is supposed to be an improvement over the 9-cell GE approach. Just as in the previous approaches the cycles represent the sizes of the industries involved and the pie wedges denote the business market share.

In the Table above, A would appear to be a developing winner and C would be a potential loser, E is an established winner, F is a cash cow and G is a loser or a dog.

The strength of the lifecycle matrix is the story it tells about the distribution of the firm”s business across the stages of the industry evolution.

It should be noted that each of the matrix types has its pros and cons.

Thus, there is no need to vehemently insist on the choice of the matrix to use.

The business unit competition position

The most important thing is to have a good analytical accuracy and completeness in describing the firm”s current portfolio position just for the purpose of knowing how to manage the portfolio as a whole and get the best performance from the allocation of the corporate resources.

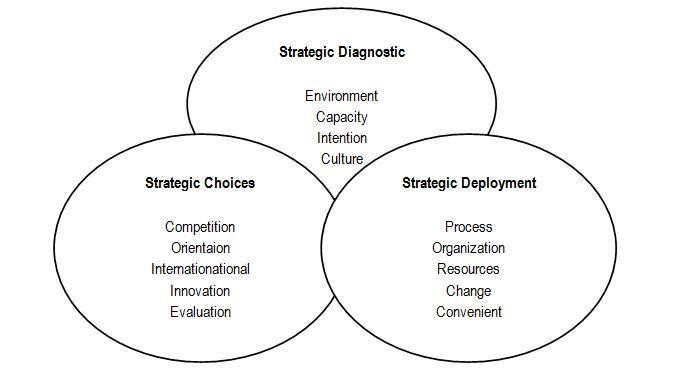

The construction of business portfolio matrixes has been identified as the step in evaluating diversified forms of current strategic situations. This is because of the insight and clarity they provide about the overall character of a firm”s business build up. However, business portfolio analysis does not constitute the whole corporate strategy evaluation process. A business portfolio matrix offers a snapshot comparison of different business units and some general prescriptions for the direction of the business strategy.

But this is too simple a framework on which to base long-term direction setting, make strategic decisions and allocate huge corporate resources. In light of this, more probing into the status and prospects of each business unit in the portfolio is needed to guide corporate strategy decisions. The needed probing required has been well explained by Hofer and Schendel (1978). The steps involved include these.a. Construct a summary profile of the industry environment and competitive environment of each business unit.

b. Appraise each business unit”s strength and competitive position in its industry; understand how each business unit ranks against

its rivals and the key factor for competitive success. This affords corporate managers a basis for judging the business unit”s chances for real success in its industry.

c. Identify and compare the specific external opportunities threats and strategic issues peculiar to each business unit”s situation.

d. Determine the total amount of corporate financial support needed to fund each unit”s business strategy and what corporate skills and resources could be deployed to boast the competitive strength of the various business units.

e. Compare the relative attractiveness of different businesses in the corporate portfolio. This includes industry attractiveness/business strength and a look at how the different business units compare

on various historical and projected performance measures such as sales profit margins and return on investment.

f. Check the overall portfolio to ascertain that the mix of the businesses are all well balanced, i.e. there are not too many losers or question marks, not too mature business that can slow down corporate growth. But there should be enough cash producers to support the stars and develop winners, too few dependable profit performances as suggested by Thompson and Strickland (1987).