Arising from the corporate nature of Zambian communities that were held together by a web of kinship relationships and other social structures, almost every form of evil that a person suffered was believed to be caused by members of his/her community. There is no event without a spiritual/metaphysical cause; hence people looked beyond physical events to their spiritual etiology. This situation arises out of the nature of the African continent.

Droughts and floods, sickness and health, rich harvest and poor crops, high infant mortality, and so on, lead naturally to the externalisation of cause and effect and to the postulation of agencies more powerful than a human. Against this background life was uncertain, and people looked beyond themselves to solve its riddles and to be ensured of stability.

Every form of pain, misfortune, sorrow or suffering; every illness and sickness; every death, whether of an old person or the infant child; every failure of the crop in the fields, of hunting in the wilderness or of fishing in the waters; every bad omen or dream: these are all the manifestations of evil that human experiences are blamed on somebody in the corporate society. As a result, young people in Zambia were taught strictly how to observe the religious rituals, ceremonies, laws, and avoidance of taboos, for the sake of their own survival.

Sin and Salvation

The concept of salvation among African traditionalists was determined by what one was saved from. Africans conceptualize sin in terms of “big sins” and “minor sins”. Big sins are listed as violations of tribal taboos or revealing to women and the uninitiated the secrets of what takes place at initiation. Small sins include trespassing on a neighbour’s property, failing to care for a neighbour’s stock when the need arises, child abuse, and bitterness. Punishment for big sins varied from drinking human waste matter to capital punishment.

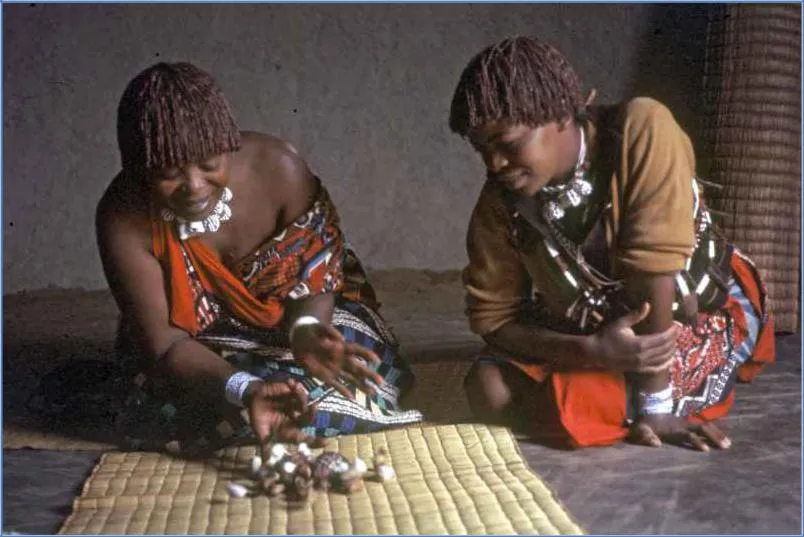

Sin from an African viewpoint appears to be an anti-social act, and salvation can only be obtained by satisfying social demands. For example, when a person was caught with someone else’s wife that person was required to pay damages or a fee and in addition, a white chicken had to be slaughtered in order to reconcile the two people through the shedding of blood. A white colour signified the purifying of the consciences of the offender and the offended. Young people were religiously instructed that to be saved, therefore, was to be accepted first in the community of the living, then in the place of the dead.

Death and theAfterlife

Most Zambian tribes possessed myths explaining how death first came into the world and one of the most fundamental features of traditional life was the relationship between the living and the living-dead. People accepted death, but every human death was believed to have external causes. People had to discover and state the causes of death. These causes were said to be the results of magic and witchcraft or spirits who were offended and bore a grudge, or from a powerful curse.

One or more causes of death were to be given. Though death was accepted, it could be prevented because it was always caused by another agent. At death a person went to join the “shades” or “living-dead”, for as long as he/she was remembered by those who remain. During this time, usually three or four generations, the person might visit his/her former home and see his/her relatives and was thought to have a real interest in the welfare of the family and clan, and to hover around the community.

However, there is a sense of separation. People cannot say to him/her, “Here is a seat, sit down and let us prepare a meal for you.” She/he appears only to one or two members of the family, particularly the older ones and enquires about the welfare of the others. She/he cannot participate fully…but his/her appearance strengthens family links between relatives in this life and those in the spirit world.

Among the Lamba people in Zambia, an individual is understood to be made up of three parts: body, person and spirit. “When a person dies his/her body is buried; himself/herself goes to ichiyabafu(the abode of the dead), and his/herumupashi(spirit) returns to the village to await reincarnation”. Traditionally, when a good person dies his/her spirit is thought to come back in one of his/her sisters’ children.

As a result, his/her sister’s children are in some respects more important than their own. “If the birth is normal it is the maternal grandmother who decides upon the name of the child. Should the child fall sick after a day or two, or even a week, the people say, she/he has refused the name” and another name is chosen. Hence the practice of waiting a few days before naming a child is practiced so that one can see who she/he is like in terms of disposition.

In Zambian culture the issue is not the afterlife but the way in which the living dead continue to be involved in life among the living. Interestingly, the Lamba people in Zambia used to burn witches and wizards because they believed that fire was one thing that could destroy the spirit. As far as death was concerned, young people were taught to religiously maintain offerings of food, animal blood and any other accepted sacrifices as well as to engage in consistent prayers and observance of proper religious rites to avoid unnecessary death.